We will never have another Christmas like the Christmas of 2004, when we went to visit my sister, Kate, during her stint in the Peace Corps in Morocco. It was, like the original, an epic journey with gifts brought from afar. There were donkeys, and innkeepers (though ours had plenty of room). There was snow and presents and joy. There were no infants, but Darcy did give a gynecological exam to an eight-month pregnant Berber lady.

On Christmas eve morning we awoke in Marrakesh, had a quick Petit Dejuener at an outdoor café, with the usual spread of coffee, omelette (just eggs, really), pan with butter and jelly, and jus du orange. These cheap, satisfying continental breakfasts were always a sane, civilized, comfortable way to start a day that was likely to be insane, uncivilized, and uncomfortable.

Even before 9 am a few hustlers and showmen were already at work in Djama El Fna, the open, mostly deserted plaza that had been a smoky, teeming street fair just hours before. A snake charmer tended to his serpents as a cat (probably on the payroll) displayed curiosity bordering on idiocy, stalking in way too close to the blanket of cobras.

I wanted to take a picture, which meant I was obliged to give the man a few Dirham, which meant he had to grab a Cobra and insist that he touch its belly to my forehead, for good luck. I have always been wary of snakes, and, just a few days into our trip, I felt the same way about Moroccan men. But neither phobia was irrational, and to prove it, I was going to stand still and let the charmer put me in his act. As soon as the snake and I touched, I instinctively started to pull away, but the snakemaster was going to punish me for falling for the oldest trick in his book, and he wrapped the cobra around my neck like a cool, slimy scarf. I wouldn’t say I freaked out (Darcy would), but, if it had been an audition for the part of Cool Hand Luke, I wouldn't have gotten the part, not even a callback.

Another day in Morocco had begun. We took a Petit Taxi to the outskirts of the city to buy wine and spirits and real cheese at the one place in Marrakesh where you can find such things, the Marjane. Petit Taxis really are truly petit, little 4 door hatchback Peugeots that you could easily pick up and toss in the back of a Ford F-150. The Marjane is like a Walmart/Grocery Store in one, but after a few days in the dark, winding souks, with no center and nothing super about them, it was like a morning tour of heaven and hell. We soaked up the flouresecent rays, and eventually secured 560 Dirhams worth of whiskey, wine, Camembert, veggies, pasta, and chocolate, and stuffed it in our backpacks. We would be hauling it for Christmas Eve dinner in Ounsghart, a small Berber mountain village at the top of Kate’s valley, tucked beneath the jagged peaks that make up Toubkal National park. Darcy and I had no idea how far it was, physically and psychologically, from the Marjane to Ounska, but we would soon find out.

We took another Petit Taxi to the airport, where Kate’s bag of presents from home, misplaced three days earlier by Royal Air Maroc, was supposedly ready to be picked up.

The lost baggage line was not too horrible, although the unusually chubby and cheery Moroccan behind the desk was certainly taking his time, saying way more than one would think needed to be said considering the business at hand. When it came our turn, he told us, in near perfect English, “I’m sorry, I don’t speak English. I only speak Arabic.”

Frowns. Beat. Smiles. We laugh. Good one.

We gave him our tickets. Some clicking of the computer, then another frown.

“Your bag is not here. It’s in Marrakesh.”

I was furious, but I tried not to sound it. I didn’t want lose my cool and be an ugly American. Firmly, “We called here this morning. They said the bags were here. Are you sure?”

Kate pointed out that this, was, in fact, Marrakesh.

“Oh, yes, my mistake,” he said, eyes atwinkle like Saint Nick.

“Aaah,” I said, pointing at him, very mildly amused, “You.”

He walked around us, opened a door, put his finger against his nose, and there lay the bag, a Christmas miracle. Even more miraculously, it was just as full as when we put it on the plane. Kate’s new used Imac was still wrapped in her new fleece pajamas, packed in with lots of other warm presents, even the red, white and blue book with “America” in big block letters on the front, everything had made it past customs and thieves.

This was no small thing, as the Moroccan custom sieve can be oddly selective. Months earlier, Kate asked for a globe from home, perhaps to try to show her villagers what color their country was, how many centimeters they were from more influential countries, etc. My mom found an inflatable globe, perfect!, and sent it hurriedly, happy to be of use. A few weeks later, Kate was called down to Marrakesh and scolded severely by some customs agents. Her crime? The globe, which they had taken upon themselves to blow up, did not clearly demarcate Western Sahara, a long disputed spit of desert land south of Morocco, as being part of Morocco's domain. The globe was taken away, tortured, then punctured repeatedly. Later, a friend of my mom’s found a globe that did show Morocco and Western Sahara as being lawfully united, and sent it on to Kate. Again she was summoned to Marrakesh, scolded, and not allowed to take her toy with her. This time, the agents mistook the Tropic of Cancer for a lie of the West.

So, getting that bag back, with everything in it, was a good start on the road to Christmas.

We crammed our stuff and ourselves into another Petit Taxi, and it was off to the Grand Taxi stand to find a ride up to Asni, the commercial center at the base of Kate’s valley where the Grand Taxi’s stop and the mountains begin.

We let Kate choose from the fleet of drivers and their tan 1970’s Mercedes sedans and negotiate the price.

Kate was our interface, she had the languages (French, Tashalheet, and some Arabic) and the chutzpah to get deals done. We were fine with that, until the taxi stand, where, with dozens of waiting taxis to choose from, she led us over to one Mercedes and began talking Tashalheet business with a man who was staggeringly drunk, in any language, at noon.

“Kate,” Darcy and I both said sharply, “That guy is not driving us. He's trashed.”

She wasn’t sure if he was, but a few moments later it was determined that he was merely one of the driver’s entourage, a relief, though still not encouraging. She reported that we would be heading up to Asni as soon as the taxi was full.

The three of us and 1 driver seemed plenty full to Darcy and I. This was a mid-sized sedan, not a limousine, but Kauotar explained the way things worked: one bought a share in a Grand Taxi for 12.50 Dirham, and there were six shares in every cab. That meant two in the front with the driver, the middle-man trying not to get impaled on the stick shift, and four in back, squished together like a package of weiners for the 45 minute, 45 kilometer ride.

“Could we just buy out all six shares?” I ventured. “We kind of need to get going, don’t we? That would be like, what, nine bucks?”

This was a possibility, Kaoutar admitted, reluctantly. She didn’t like thinking in bucks, she had spent the last months adopting the mindset of a poor Berber wench who needed to pinch every last Dirham. Peace Corps volunteers are supposed to live among the people, not go bling-blinging around in taxis only 4/7ths full. I insisted that we get our own cab, I would pay for it, even though Kate was disappointed that we wouldn’t fully “experience” a Grand Taxi, Berber style.

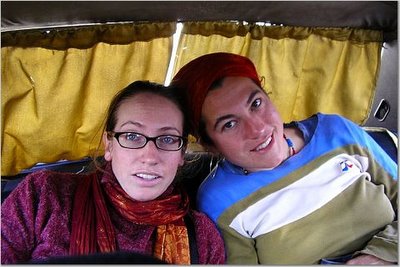

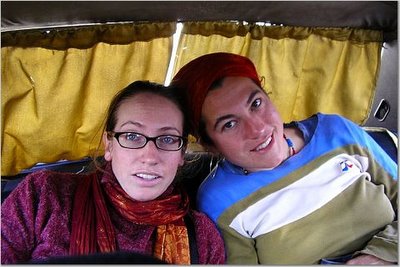

The ride was plenty experience enough for both Darcy and I. While Kate wished we could all have a Berber buddy in our lap, all Darcy wanted for Christmas was a seatbelt. She has always been safety-minded, and, even though this driver was not as reckless as some we’d heard about, a ride in a Third World country without a restraining device was, adrenaline-wise, like day at Six Flags for her.

While Darcy dug her nails into Kauotar’s knee in the back, I was content to experience the sights and sounds of the Moroccan roadside and countryside without the pressure of a Moroccan against my ribs. The taxi lacked not only seatbelts, it had no functioning –ometers of any sort, and the windows didn’t roll up. It did have handsome curtains covering the rear window, however, and it had a functioning tape deck, which provided a nice backdrop of Berber music for our ride through the fields and up the pink, stony hills into Berber land. Twangy, snaking guitar melodies were laid over layers of goat skin drums, with Tashalheet vocals that occasionally leapt into a alarmingly shrill “Le-le-le-le-le-le-le-le-le…”

I asked Kate if that was a human making that noise, and, if so, what it signified. She said Berber women made the shriek, she’d even seen it done at weddings. She didn’t understand all the lyrics, but you could count on Allah getting praised in most songs. There were some love songs, as well, she had deciphered a few lines, like:

“I saw you in the fields,

I asked your father about you…”

As the Berbers sang, drummed, and picked, I observed a lot of folks in the fields, and gazed at the amazing amount of life visible from the cab window. Cart-pulling donkeys were beaten by stick-wielding boys . People were riding mopeds and donkeys Moroccan-style, which meant overloaded, with both legs nonchalantly swung out over one side. Women hauled giant bags of supplies on their heads, or enormous bundles of firewood on their backs. Gendarmes stood in the middle of the road, crisply dressed in blue uniforms and white caps, looking well-groomed and vaguely malicious, eyeing the nervous motorists, searching the stream for an unlucky suckerfish to reel in and shake down. Blue and rainbow painted camion trucks were packed in like dumpsters with supplies, livestock, and passengers peeking their scarved and hooded heads over the rail. Stray dogs roamed freely, scouting the herds of goats and sheep, and clusters of chickens. I was struck, not for the first or last time, by the omnipresence of people in the landscape, no matter how remote or harsh. It was a remarkable sight for Long Islanders who exist primarily in their homes, offices, and cars, and only go outside occasionally, in nice weather, for a jog or to walk the dog. I can drive all day and see maybe a handful of humans on the side of the road. In Morocco, men, women, and children, (but especially men) “gare” or sit… against walls, under trees, or on their favorite rocks in the middle of fields, near no structures or landmarks.

Adding to my enjoyment of the ride were the warm rays of the sun on my arm after two days and nights of shivering in Marrakesh. I was down to a single layer, no long underwear or undershirts. When we left JFK it had been 20 degrees, but in the First World, one merely darts from one overheated enclosure to the next, with thick overcoats to ward off the cold in the moments between.

Marrakesh never got below freezing (we saw signs of thermometers or weathermen, so I can’t give a figure), but the cold was creeping and relentless, intent on worming its way into our guts. The buildings had no heat, and their construction, designed to temper the brutal heat of the summer, turned most indoors into stone and tile ice-boxes. We had blankets, and we had brought lots of layers, but, when the clouds thickened, or a wind blew, or a mist descended, or night fell, we always felt one layer naked, chiding our naïve selves for leaving packing our bathing suits and leaving our ski jackets at home.

The midday winter sun, making its first appearance since we’d arrived, worked wonders. For an hour or two we could unclench our shoulders and thaw our tense jaws. But, by the time we reached Asni, plotting clouds had recaptured the sky, and we were forced to put on more damp layers, with the knowledge that things would only get colder as we went up to 7000 feet, and evening settled, and the weather worsened, as it appeared intent on doing.

We had tea at a grungy café in grungy Asni, surveying our new surroundings and asking Kauotar to detail our plan. We were to take another cab to Imlil, a trekking base town further up the valley where the paved road ends. There we would meet Chris, another Peace Corps volunteer, who was staying with the Frenchies and waiting for us, then either hike or take a camion over the pass and down to Ounsghart, where we’d uncork our bottles and celebrate Christmas Eve in a purely secular manner.

What to do with the big black bag of goodies? Kauotar arranged to leave it with her friend, the cafe proprietor, Mohammed, who would find a local Santa to deliver it to her door in time by Christmas morning. I was dubious, but Kate assured me it would get there, although she did pop into a hanut to buy a little lock for the bag, just to keep curious eyes out.

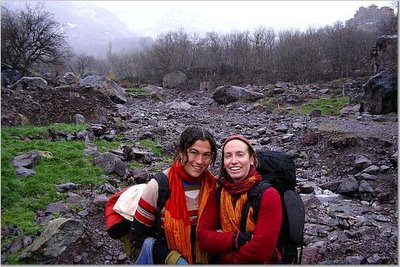

As we taxied again up to Imlil, the weather turned downright raw, worse than anything in Fez or Marrakesh. The afternoon drizzle morphed into fat snowflakes. Our breath came out in thick, milky white plumes. Our walk through town wound us uphill, over a creekbed strewn with wet, cold, grey boulders, past a mass of gawking children, then to a schoolhouse door, were Kate knocked, and mercifully, one of her Frenchy friends in a Djallaba let us in.

The Frenchies were lounging about cross-legged blowing cigarette smoke out of the corners of their mouths. They had a computer, speakers and all, playing funk music. Their décor included a poster of James Brown, lots of pictures of them and their jazzy Frenchy friends traveling around the world. They even had a dartboard. They were blasé about our arrival, greeting us limply, then returning to planning their Christmas Eve dinner.

The one Frenchie who was sweet on Kauotar was nice enough to make us coffee, a welcome break from tea, which we enjoyed along with the effects of the small smoldering hearth fire and the electric heater, which was being hogged by a cluster of kittens. Darcy warmed up with a pair of kitties while Kate found out that Chris had already left for Ounska without us. No one was sure how long it took to hike to Ounska, estimates ranged from three to five hours. We had only three hours of daylight left, and the weather outside was increasingly frightful. No one was sure if the camion had passed through town yet, when or even if it could be expected to arrive.

We left the Frenchies and their heater, without much fanfare, if only to feel like we were moving in some direction. Some villagers told us that the camion wasn’t coming that day. Setting out on a hike this late seemed foolish. It was sad to abandon the plan of going to Ounska, especially when there was no way to tell Chris we couldn’t make it…he would sit there waiting for us, and waiting, all alone on Christmas Eve, perhaps worrying that we were buried in a snowdrift. We could go back to Kate’s village, but that seemed like a letdown.

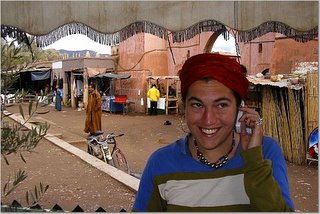

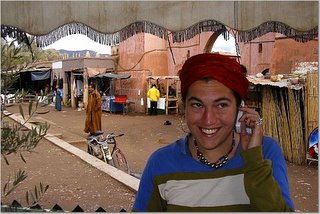

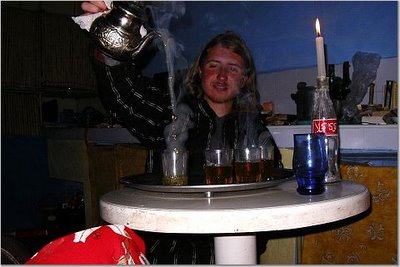

Kate spotted a friend, a young, Berber trekking guide dressed enviably in Patagonia trekking pants, a North Face parka, a hat and gloves, all of which he had swapped from European clients. He was very friendly, a big fan of Kaoutar’s, and he suggested tea at a concrete café. There was no heat of course, but at least we’d have a roof over our head as we waited for the camion, which he seemed to think would show up anytime. It was a quintessential Moroccan moment, combining the elements of tea (our third round of hot beverages in as many hours), shivering against the cold, language potpourri (our conversation was a goulash of French, Tashalheet, English, even a little Spanish), killing time (a group of five young men sat with their backs pressed against the back wall of the café watching some American B-version of “Cocoon”), and uncertainty about where we were going and when (and if) we’d get there.

I got up to go look at a shop across the street just to get my blood moving. Just then, a blue truck with rainbow painted cargo hold came rattling up the road and stopped a few yards up from the café. Le camion! Christmas was saved again.

Like the overcrowded taxis, the mountain camion ride was on the list of things Kate wanted us to “experience”, and this time, we got the uncensored version, if not the director's cut. The other 5 or six riders were kind enough to let us soft Americans take the seats. Of course, much to Darcy’s dismay, not only did the camion lack seat belts, but our “seats” were three of the 40-odd propane tanks (Berber cooking fuel) that made up the bulk of the camion’s cargo. Our companions leaned against the back gate, smiling and assuring Darcy that all was well as we rollicked from one switchback to the next amidst the clanking of metal barrels. A blue tarp had been strapped over the top of us to keep the elements out, so we couldn’t see much. This was probably a blessing, since what I could see from the narrow triangle out the back was blowing snow and whitening mountainside, both at distressing angles.

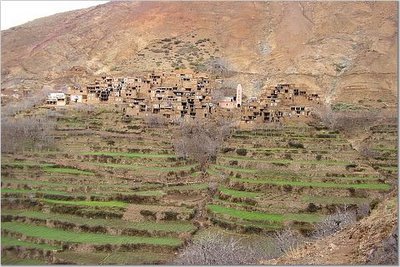

About halfway through the 45 minute, 11 Km ride, we stopped to unload and load some goods at a hanut (store) at the edge of a dizzying cliff, with no potential customers to be seen anywhere. I got out to take pictures. After getting my first good look at the road we were on, covered now with six inches of fresh snow, barely wider than our vehicle, and flanked by a cliff that ended somewhere underneath a mat of clouds below, I reluctantly got myself back in the truck.

We started bouncing along again, and I decided to stand and look out back with the other boys, my last vision on earth was not going to be a blue tarp. Two Berbers were running after our tire tracks with shovels, in case we got stuck. We lurched and the bald tires spun, just one unfortunate spinout or lurch away from a metallic, crushing death. I told Darcy she was lucky she couldn’t see what I saw, which was not a good way to ease her worries. After half a mile of this madness it was my voice insisting with very unmasculine high-pitched whine: “Kate, let’s walk from here.” After no response, even more shrill, “Tell them we want to get out and walk.”

She teased me later, saying I was crying (I wasn’t crying, yet), but she herself was pretty quick to pass my request on to the driver, and we all were happy to see that truck go around the next treacherous bend without us in it. We had originally intended to walk anyway. The way to Ounsghart was all downhill from there, and the weather was frigid, but clear, allowing a breathtaking view of the peaks above and the valley far below. No sense risking a caged demise, tenderized to death by propane canisters, when we could enjoy such an invigorating stroll. We jogged through the snow to beat the cold and the oncoming dusk, and arrived at the next hanut as our camion was still unloading bundles of vegetables and sacks of flour.

We found our packs, and followed some boys on donkeys down the footpath into the village in the fading light. We entered a doorway with a sign and ducked through a hallway to emerge on a patio, where the jite (inn) owner, Chris’ host brother, Lashin, fetched us some plastic patio chairs and some mint tea, our fifth round of the day. From a dark room to the left of the patio, Chris emerged in his custom-made pinstriped Djallaba and informed us that he was in the midst of a village meeting re: plans for the new loom and hammam (bath house) that were in the works thanks to his Peace Corps efforts.

We stayed outside, the cold quickly seizing our bones again after our briefly reviving cross country run. We were glad to see Lashin bring out bowls filled with steaming broth, but when he was out of earshot, Kate said, unenthusiastically, “Looks like Cream-of-Blank soup” a flavorless favorite from her village. It turned out to be the even blander, starchier Ounsghart version, Berber Flour Soup, (quick recipe: mix flour, water, salt…heat, enjoy!) which tasted and felt like warm glue going down. I’ll eat just about anything, yet, despite its much-needed warmth, and my hunger, I couldn’t make a dent. We were all very happy when the meeting adjourned and Chris led us into his room to warm up and get the party started.

In the wee, wee hours of Christmas morning, I found myself staring into the pitch dark of Chris’ tiny room, feeling wide-awake and slightly nauseous from some combination of the tea, the tagine, the whiskey, the wine, or perhaps the carbon monoxide which had set off Chris’ detector twice through the night (causing Chris to get up and crack a window).

Darcy and I were on a pile of mats on the floor, under mountains of blankets. Lashin's “jite”, was a mountain bed and breakfast of sorts that makes a cheap hostel look like a grand hotel. His establishment provides weary trekkers (few to be found that time of year) with tea, food, blankets, and one of a dozen mats on the floor of an otherwise empty room. At bedtime, the jite room was just too cold, so Darcy and I decided to sleep on the floor under a pile of blankets and on top of a pile of mats in Chris’ rented room, with Kate and Chris on the wallside couch/beds above us at right angles to one another. A cozy little place to sleep on a cold night...or lay awake staring into the dark.

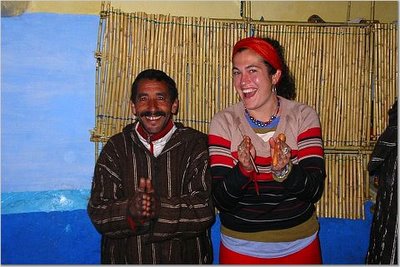

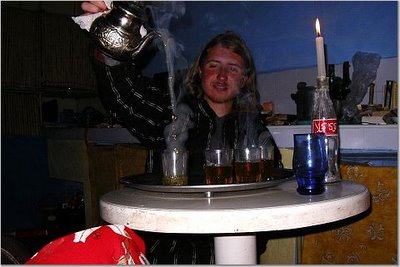

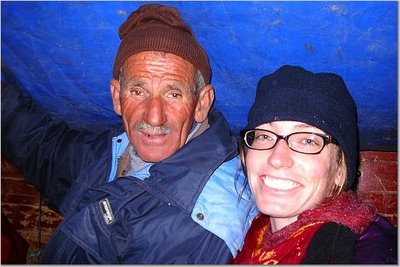

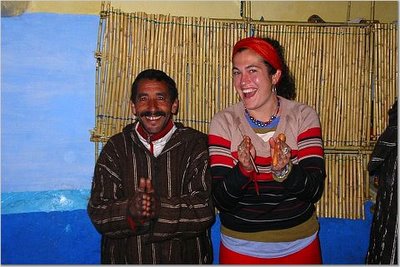

I had a headlamp, but I’d wake everyone up if I turned it on to read. The party had been fun. We had unpacked our goods from the Marjane, like treasures from exotic lands considering the distance we had come. Kate made a fine dip for the artichokes, and we ate every last bit of our cheese and crackers. Chris sent a Berber kid out to buy a freshly killed chicken, and he and Kate worked together to make a mean Tagine. Lashin showed up, and Muslim or not, drank more than his share of whiskey. He only spoke Tashalheet, but we all got along well enough. He brought in a tiny boombox with Berber music and we had some lessons in Berber dancing (it involves a lot of shoulder shrugging for boys) and Berber clapping, which is maddeningly off Western rhythm.

We finished our booze, ate our Tagine, smoked Lashin’s cigarettes, had tea #6, probably what was keeping me up now, and went to bed. What a day! And it was still going, four hours until a hint of light crept through Chris’ wooden shutters and I decided I was better off outside.

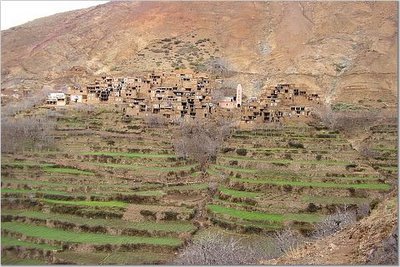

It was fantastic out there. A White Christmas like none I’d ever seen. An inch of powdery snow had fallen on the patio overnight, and it blanketed the sharp stupendous peaks that towered in every direction, and the rooftops of the ancient-looking Berber village, and the terraced fields across the river below. The sky had cleared, except for a mantle of clouds ringing the peaks to my left, up the valley and into Toubkal Park proper. To the right, downriver, loomed “The Mountain That Speaks To You”, stark, lonely, and dramatic.

I bundled up, thought about writing in my journal, but eventually just sat, like a Berber man, letting the mountain speak to me. Unfortunately, my GI Tract was also speaking to me, and the pure crisp air and the stunning vistas couldn't quite calm my churning stomach.

Two days before I had stopped in La Mamounia, the swankest hotel in Marrakesh, to use their facilities, but I was already in the swankest hotel in Ounsghart. The problem was, whenever I approached the “bathroom” (a filthy porcelain ground sink with a hole, two footrests for squatting, and a faucet with a bucket for flushing) the odor heightened my nausea, and I lost my nerve.

Finally, I took a deep breath and confronted the problem, and the morning brightened after that. Chris came out and joined me just as the sun came up over the peaks to our left, warming our thankful faces. From the patio I watched the village come to life, mostly in the form of Berber boys, 6 to 10 year olds, shoveling off the rooftops with wood shovels that looked like picket signs, before the snowmelt leaked through the earthen roofs. I watched, a little guiltily, as Lashin’s young sons shoveled our patio. When his daughters, 6 and 8 maybe, got involved, pointlessly sweeping up the corners with a little hand brooms, I really felt I should help, but Lashin was sitting there watching himself. His culture dictated that kids worked while adults watched, and besides, it was a holiday for me. It isn’t so terrible, really. Kids have boundless energy, which they usually use to dart around aimlessly, shrieking and irritating us all. Why not harness the renewable energy and wear them out with some shoveling?

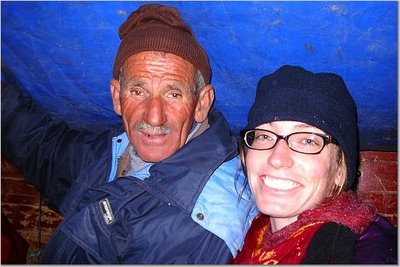

Kate and Darcy emerged last, and shortly after they had cleared the sleep from their eyes, they went inside with Lashin’s wife and my headlamp, Darcy to give a gynecological exam, Kate to translate. The night before, we had asked Lashin how many kids he had. He said 6, maybe. He had five, and his wife was 8 months pregnant, but she had been sick lately…unable to eat, weak, rashes. They had been down to Asni once to see the doctor, but it hadn’t done much good, and now it was too far, 25 Km by camion, donkey, or foot, and too late to seek anymore medical help. With the whiskey it came out that Darcy was a medical student, and Lashin, to my surprise, asked if she could take a look at his wife. She said sure, and now, with her looking a little bit queasy herself, he was holding her to it.

Chris and I waited for the girls for at least an hour, it was hard to say how long without a watch. We garred on the patio with Lashin, and got into a few snowball skirmishes with his kids and some more distant targets in the village. We took in the view from every angle and Chris pointed out routes he wanted to telemark ski once he got all his equipment. He seemed well-suited for this remote alpine existence, he was a mountain kid himself, from Wyoming.

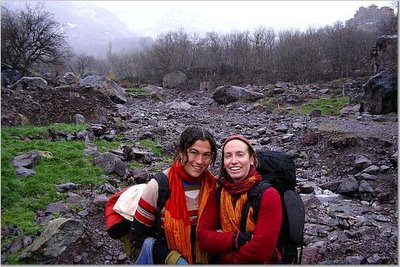

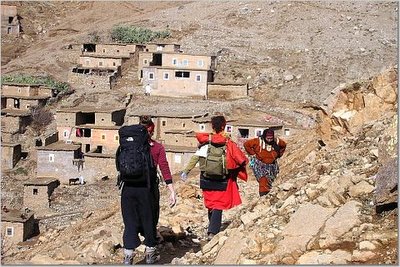

The girls finally came out of the examination room, trying to look like they gave backcountry gyn exams everyday, and we packed up and struck out on the path down to Tanasghart.

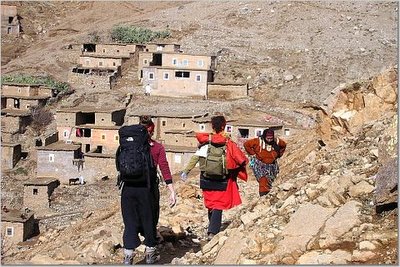

Chris and Ounsghart disappeared after a few bends in the trail, and we shut up and enjoyed the scenery . We followed a pleasant downhill grade cut into the steep slope of the North side of the valley, a few hundred feet above the river. We passed the Mountain That Speaks To You, we passed goats and sheep and their lone herders. The landscape rivaled any of the great parks of the US West, with the fascinating addition of the Berbers and their villages, which all seemed to come from a different planet than the one we thought we lived on. The villages were closely packed clusters of adobe-like rectangular dwellings wedged into, and barely discernable from, the hillsides. The communities were reminiscent of the remnants of pueblos in the American Southwest, but these were living breathing communities, crops and livestock in the terraced fields, smoke coming from the chimneys, laundry drying in the sun, which, for its usual allotment of 2 or 3 hours a day, was dethawing us.

We saw no other Western trekkers on the route, just Berbers going from one town to the next for business or pleasure. We passed countless children, most of whom tried to score a flip of candy or money with the call of “Bonjour. Bon-bon? Dirhams?” Apparently the bleeding heart French trekkers had turned these kids into beggars. We had no Dirhams and no bon-bons, and these cries, heart-wrenching at first, got a little bit irritating, especially when small flocks of kids catcalled us and followed us along the trail.

Also annoying was their reluctance to have their photos taken, due to some variation of Koranic law equating image with soul. I was trigger happy, and I thought the law rather asinine, so I took to covert methods: hiding behind rocks, nonchalantly shooting from the hip, sniping from afar on full zoom, or pretending to have Kate and/or Darcy pose for a picture, when I was really after the Berber family on the roof behind them, or the elderly Berber woman hunched underneath a load of brush twice her size, or the goatherder posing in cape and cane on a rocky outcrop. When I was caught trying to steal souls, however, nothing was more humiliating and infuriating than being scolded by finger-wagging children, “No, no, no, no, no!” My best close up was of one girl, no more than 3, left alone by the trailside, too young to chide me. Sadly, I chopped her head off. (In the picture.)

In between villages, the valley landscape grew more forgiving, the walls less steep and barren, morphing from snow-capped white to volcanic black, through a range of sandy earth tones, to the Sedona-like red rock that marked Kate’s neighborhood. Our legs had grown tired after 4 plus hours, but the hike never ceased to fascinate and keep us moving around the next bend. One village short of Kate’s, people began to recognize her and point: “She’s from Tanasghart.” Finally, we trudged into Kate’s village, looking forward to a change from sweaty dirty clothes to dry dirty clothes, and to swap blistering boots for some slippers.

Kaoutar lived on the far side of the douar, and it soon became apparent that we were farther from home than we thought. Dozens of human obstacles stood in our way on every doorstep right and left of us, all of them jobless, all of them hospitable, all of them wanting to make some tea for Kaoutar and her friends and shoot the breeze awhile. So this was what celebrities must feel like on a Sunday morning when they just wanted to go out and pick up the paper and half a dozen bagels. We didn’t want to offend Kaoutar’s people, but damn were we tired. If we weren’t a little rude, it could take us another 4 hours just to walk the final 300 yards across town. We kept smiling, waving, but moving forward, trusting our momentum would pull Kate along, but we lost focus for a second and lost her to a cluster of post-teen girls.

After a few minutes, Darcy literally grabbed Kate’s hand and pulled her down the road. Kate finally pointed out her house, and our feet were crying tears of joy and pain as we rounded the corner to the entrance to her apartment out back, where we were ambushed by a cluster of clucking ladies, Kate’s landfamily, and we were swept in for tea on tiny chairs in the cement-floored kitchen, smiling and watching Kate recount our long day’s journey, 10 meters from finished, as her blankets, beds, couches, and bag of Christmas presents lay waiting.

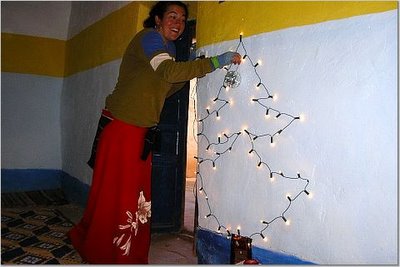

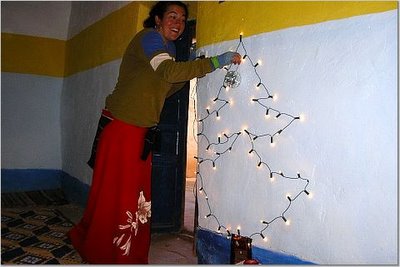

But a little tea and bread and welcoming did our spirits well, and Christmas was all the merrier once we finally got to change, and put our tired feet up under lots of blankets and watch Kaoutar, the poor Berber girl, open present after present from far off well-wishers, and seem genuinely delighted by them all.

.JPG)